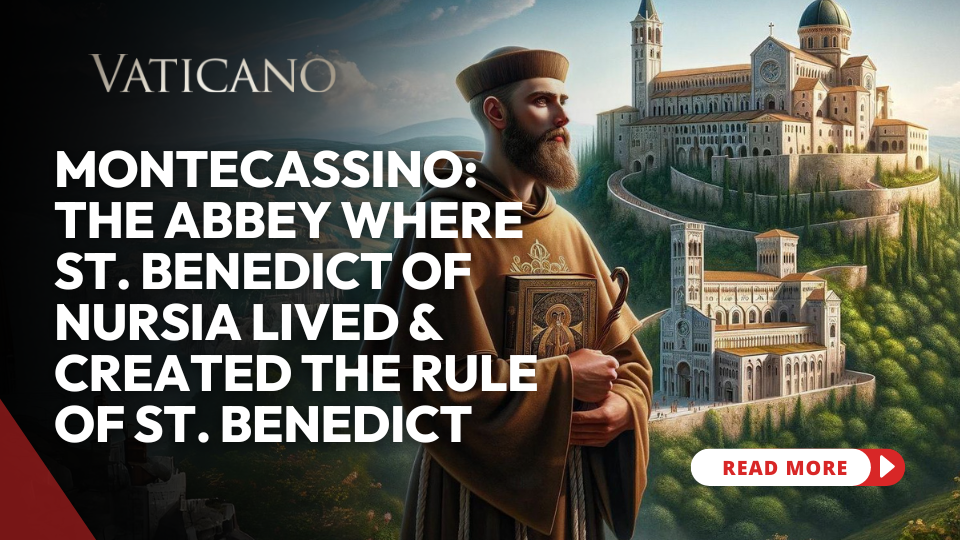

EWTN Vatican traveled to the Abbey of Monte Cassino, south of Rome, to meet Dom Luca Antonio Fallica, the 193rd successor of St. Benedict.

Dom Luca explained, “We know that Benedict came to Monte Cassino from Subiaco where he had begun his monastic life first in an eremitic form and then cenobitic form with a community. Because of the jealousy of a local priest, Benedict decided to leave Subiaco with a group of disciples and arrived at Monte Cassino around the year 529.”

Following the destruction of the Roman acropolis and pagan temples dedicated to Apollo, St. Benedict began construction of various oratories, dedicated among others to St. Martin and St. John the Baptist. In this first monastery of the order, St. Benedict wrote down his renowned rule, shaping a monastic life centered around prayer, work, studies, and hospitality.

Dom Luca explained further, “Then, first and foremost, during the Carolingian epoch, thanks to the work of Charlemagne and Saint Benedict himself, the benedictine rule got diffused and eventually became the unique rule for western monasticism. From that moment on, Benedictine monasticism born here at Monte Cassino also began to assume an important unifying value in the monastic experience during the reign of Charlemagne and in subsequent eras.”

The ecclesial and political influence of the Abbey peaked in the 11th century during the time of the great Abbot Desiderius, who later became pope Victor III, and who not only rebuilt the Abbey and re-established monastic discipline but also saw to it that the monastery library became one of the richest in Europe, by collecting and translating manuscripts from all cultures, nations, and times periods into Latin.

At the Abbey, Dom Luca explained, “We have two places where we preserve the literary patrimony. The first place is the archive where all the old manuscripts are, and the other is the library, which is where we are standing right now, where all the printed books are. We have what we call an ancient source, which is the one we are looking at right now, and which is composed of over 32.000 volumes. By ancient sources we mean incunabula, that is, books printed after the inventions of the press by Gutenberg and all the way until 1830.”

However, the preservation of the many literary and cultural treasures of the Abbey proved not to be an easy feat. Throughout the centuries, the abbey suffered several destructions, such as by the Lombards in 570, by the Saracens in 883, and by an earthquake in 1349. The most notable destruction, however, happened 80 years ago, in 1944, when the monastery was bombed during the second world war.

“The zone where the monks lived,” Dom Luca told us, “the oldest part of the monastery where the cell of St. Benedict was located, was saved from the destruction, and so neither monks nor civilians died there as they did in other zones.”

Further, Father Abbot explained, “The burial place of St. Benedict and St. Scholastica was somehow miraculously saved. The place was saved because a grenade that fell there didn’t explode.”

Tragically, he continued, “There was loss of life. And then, of course, for the symbolic value which the Abbey represented, certainly this was an event that in some way had a big emotional impact, certainly for this territory and the Abbey itself, but also for everything that the Abbey represented in Europe and beyond Europe.”

Thanks to the help of German priests, most of the Abbey’s literary and artistic treasures, including those from different national museums that had been sent to the Abbey during the war for protection, were evacuated to Rome and saved from destruction.

After the war, the monastery was rebuilt and the church reconsecrated by Pope Saint Paul VI, who also proclaimed St. Benedict a patron saint of Europe.

“St. Benedict is important,” Dom Luca expressed, “first of all, because he was a point of connection between Eastern monasticism and what was later to become Western monasticism.”

Further, the Saints marks the Christian life as a whole. “St. Benedict,” Dom Luca noted, “is also known for the famous moto: Ora et Labora, Work and Prayer, to which we can also add the imperative Read, but we could also add other verbs. I believe that beyond the verbs, it is the ‘et’ that connects them that is the most important.”

“St. Benedict,” Dom Luca believes, “testifies to the importance of a unified, harmonic life, and it is not without reason that that the Benedictine motto is pax, peace, and that Benedict was proclaimed precisely patron saint of Europe with a bull that defined him as a messenger of peace, and suggested that we can all be signs or instruments of peace in the history and in relation to others, provided that we are able to find an inner peace or harmony within ourselves.”

While the Abbey used to house over 200 monks during its golden age, the monastery is today the home of eight Benedictine monks who continue to live a quiet life of prayer, work, and studies. Despite the challenges faced by the Abbey in its history, the spirit of monasticism has persevered, and monastic life continues to flourish at Monte Cassino.

“The monasticism here at Monte Cassino,” Dom Luca emphasized, “was reborn from all these destructions. After all, the motto of the Abbey is ‘succisa virescit,’ meaning, ‘Behold a severed root blooming again.’”

Regarding the upcoming anniversary, Dom Luca expressed that, “We would like to celebrate this 80th anniversary well, since it truly indicates a rebirth. We get to look back at the destruction, but also at the new life born out of the destruction.”

Adapted by Jacob Stein